The History of Kenmare Lace

Out of Poverty

When the Poor Clare Nuns arrived in Kenmare in 1861 it was the beginning of an exciting new chapter in the life of the town. They were brought here by the parish priest Fr. John O’Sullivan to open a school. He felt that education was the best way to raise the people from their knees after the recent famine. A new church and school were built soon after their arrival. This construction provided several years of much needed employment for local tradesmen and labourers.

The works were completed in 1864, after which the workmen and their families struggled to survive. Poverty was rife, and there was no remunerative employment available for women in particular. It was in this environment that the Poor Clare nuns, under the leadership of Mother Abbess O’Hagan, set upon creating a practical course to help those in need. By establishing an industrial school in the convent building local people could gain skills which would increase their employability and improve their prospects. Young girls were chiefly employed in producing lace, though they also learned embroidery, drawing and design. The boys were not neglected, they also got lessons in drawing and design, and were trained in leatherwork, woodcarving and plasterwork.

A Commercial Success

Over time the quality of the work improved. Soon many girls were capable of earning from five to eighteen shillings a week – a considerable sum at that time.

At the convent sales figures reached £500 per annum by 1869, and it was at about this time that the production of fine needlepoint lace began at the school. Up to this point, the convent had concentrated on fine Irish Crochet lace, however, it was so skilfully designed and executed that it became known as “Point d’Irelandaise” (sic. Sr. Philomena McCarthy – ‘Kenmare and its Storied Glen’) and could be purchased in Paris, London and elsewhere.

At home, wealthy visitors who travelled “The Prince of Wales Route” (Killarney to Glengarriff) on long cars, were encouraged to call to the convent to view and purchase the lace during rest stops. At the Cork Exhibition of 1883 medals were awarded to entries from the Kenmare convent, among others. The judges felt that in general although the work was very skilfully and perfectly executed, the designs presented were not up to the same standard.

To improve matters, the Science and Art Department at South Kensington Museum, London, sent Alan S. Cole, C.B., a lace expert, to give illustrated lectures throughout Ireland. As a result of this, an art class was established in Kenmare under James Brennan, R.H.A., (headmaster of the Cork School of Art from 1860-1889). In addition, thanks to the co-operation of the Art Director at the Kensington College of Art in London, an examination centre was established in Kenmare. This was because the rules of enclosure of the convent meant that the Poor Clare nuns were not allowed to travel to sit exams.

In the years that followed many medals and prizes were awarded to Kenmare students in lacemaking competitions. They fended off entries from art schools from all over Great Britain. The Department of Education paid the school according to results and the money received was used to improve facilities. In this particularly fascinating time in Kenmare’s history, Queen Victoria ordered five pieces of Kenmare lace on different occasions. These were created from prize-winning designs. Several connoisseurs, one Mrs. Alfred Morrison of Forthill, Wiltshire and a Mrs.Winacles, the American millionairess, to name but two, placed many orders. A bed cover designed and worked especially for Mrs. Winnacles fetched £300 in 1886.

International Acclaim

Encouraged by S.C. Hall, the well-known travel writer, more and more English people supported the industry. Mr. Hall, who, up to this point, had discouraged his readers from engaging with the Church of Rome in any way, was so impressed by the work of the nuns that he composed, printed and distributed verses in praise of their work across England, and asked that Kenmare Lace and the work of the nuns be encouraged. He became, and remained until his death, one of their greatest supporters.

Many pieces of fine embroidery were also produced. A picture of the crucifixion, worked in fine linen, is so perfectly stitched that one can scarcely believe it to be embroidery at all. Sr. Bonaventure Smith was the first artist to use Celtic tracery in 19th Century ecclesiastical vestments. She made mitres for many members of the Irish, American and Australian hierarchy. Professor l’Amour of Queen’s University, Belfast came across her work in many places, and gives her honourable mention in his book on “The Celtic Art Revival”.

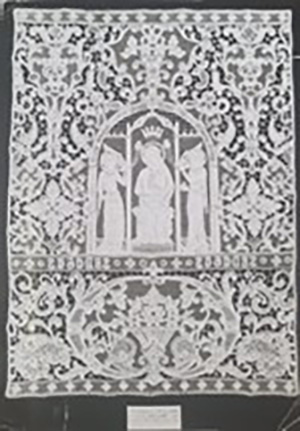

Visitors from all over the world have seen samples of the lace in museums abroad, and have traced it to its source. Take Washington D.C. for example – its National Museum holds a needlepoint hanging which depicts Eire with a round tower and wolfhound.

Highly Skilled and in Demand

Two other outstanding local lace-workers were Katie and Mary-Jane Leahy, who worked on the beautiful piece known as the Tabernacle Veil, now in the National Museum, Dublin.

With a steady flow of fees from the Department of Education, due to the nuns’ good results, the convent purchased the most sophisticated tools and equipment available at the time. With their savings, supplemented by a donation from an unknown benefactor, they erected a new wing which contained a spacious, well lit room for the lace workers, and a beautiful kindergarten. Teachers who had obtained their art certificates in Kenmare were readily employed in England, with some of them appointed “Specialist Teachers of Drawing” in certain London schools.

“King Edward VII purchased a collaret for Queen Alexandra, and Queen Elizabeth II received among her wedding gifts an antique bed-cover of Kenmare Needlepoint (lace). The Vatican has a needlepoint (lace) rochet designed in Kenmare and presented to Pope Leo XIII by the Irish hierarchy, and an embroidered mitre, presented to Pope John Paul II in 1980. I name but a few of the well-known pieces extant”. Excerpt from ‘The Kenmare Journal’ 1982.

The End of an Era

Unfortunately, with the changes in society and the economy, brought about by the war (1914 to 1918), the market for handmade lace declined. Many of the workers emigrated, but the convent lace room with its display of antique and modern lace remained in place for many years thereafter.

Timeless Designs

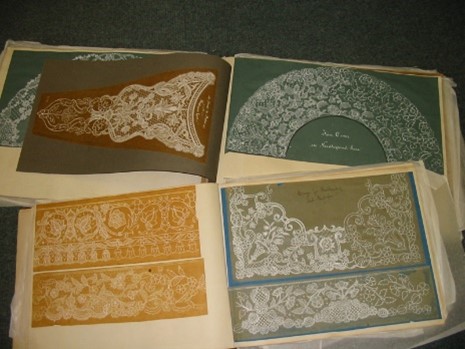

A major factor in the development of Kenmare Lace as a unique style was the development of its own original designs. A school of design was established in Kenmare which was affiliated to the Kensington College of Art in London and the Crawford school of Art in Cork. From this school came designs which won acclaim in exhibitions around the world.

Happily these designs were not lost and today they form the basis of the revival of this cherished local skill. The original designs can still be seen today at The Kenmare Lace and Design Centre.